History

The old town of Kranj - in older mentions also Carnium, Creina, Chreina, Krainbourg, Krainburg - is a historic town on the natural pier between the rivers Sava and Kokra. The area of the city center was inhabited in the Late Stone Age or Neolithic, more than 6,000 years ago. This places Kranj among one of the oldest inhabited locations and among the oldest Slovenian cities. Kranj is also the only settlement in Slovenia that has been inhabited since antiquity until today, which is why some define it as the oldest Slovenian city.

The historical landscape of Carniola is also named after the city of Kranj, which was originally its center. Kranj was the first capital of the Slovenes, as from the 8th century onwards it was the center of the Slavic principality of Carniola, which the Lombard chronicler Pavel Diakon describes with the words "Carniola, patria Sclavorum" (Carniola, the homeland of the Slavs). The city was named after the Celtic people called Karni, which are already reported by ancient written sources (Livy, Pliny, Strabo).

The oldest settlement from the Late Stone Age was, as mentioned, at the extreme end of the natural pier above the river Kokra, on today's Trubarjev trg or Pungart. Numerous pieces of ceramic vessels, bones and stone tools from the period from 4900 to 4300 BC have been found here in several archaeological excavations that have taken place since 1990. The site is comparable to nearby Drulovka, where Neolithic remains were discovered in 1955 and 1956 and are now kept in the Gorenjska Museum. The settlement on Drulovka, next to the mounds in the Ljubljansko Barje (the Ljubljana Marshes), is considered a key site, on the basis of which archaeologists have defined the culture of the Late Stone Age in Slovenia.

The Bronze Age in Kranj left no traces, and at its end (the end of the so-called urn burial culture and the beginning of the Old Iron Age or the so-called Hallstatt period, 8th century BC), an extremely large settlement was formed here, which it surpassed in size the later medieval town center. It included the entire natural pier between the Sava and Kokra, the slope to the left bank of the Sava and the area to the current Hotel Creina. They found the remains of many residential buildings, ceramic pottery and traces of metallurgical activity. The cemetery of this settlement stretched from today's Prešeren grove to the current bus station.

In the Late Iron Age (3rd to 1st century BC), settlement was obviously not as intensive, and graves from that time are known from the vicinity of the Stošič Monument on Koroška street.

The first traces of the Roman occupation can be seen in the numerous remains of quality vessels imported from northern Italy, in the first monetary finds and with individual pieces of Roman military equipment. The settlement, which flourished sometime from the 15th century BC to the 15th century AD, represented a trading post on the route between Emona and the kingdom of Noricum in the north. The first wall with towers was also built at that time. After the rise of Emona, the settlement died out, but revived in the late Roman period (4th century), when the natural protection of the place became important due to dangerous conditions.

In the 5th and especially the 6th century, Kranj became the most important settlement in today's Slovenia, it got a new wall and an early Christian church with a baptistery. The first name of the settlement - Carnium - is also known from this time. Small finds from the settlement and from the extensive cemetery on today's Sejmišče and Savska street indicate a distinctly ethnically mixed population that stayed here during the migration of peoples. In addition to the indigenous Romanesque population, many Germanic peoples (Langobards, Eastern Goths, Alamanni, Franks) left their traces. Extremely rich jewellery and military equipment belong to the social elite of late antiquity. Remains of dwellings in the form of half-earthlings have been found throughout the city centre.

In Kranj, as the only settlement in Slovenia, the presence of the Romanesque population has been proven even at the time of the settlement of Slovenes. The settlement retained its central significance even in the early Middle Ages (8th to 11th centuries). The Old Slavic cemetery around the parish church is the largest of its kind in the south-eastern Alpine area, and a not-much-smaller cemetery was also built on the right bank of the Sava near the railway station. Kranj was the capital of the then Old Slavic principality of Carniola, which included the central part of later medieval Carniola.

After the unsuccessful revolt of Ljudevit Posavski against the Franks, who were also joined by the Slavs along the upper Sava, in 828 the Franks formed a county along the Sava with their seat in Kranj with a new administrative arrangement of the Friulian mark in Carniola. The Carniola region has been one of the border counties or regions subordinated to the Duke of Carinthia since 973 (according to other sources in 976). After the separation from Carinthia in 1002, however, it became an independent border county with its own border count. The seat of the border count changed at the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries with the appearance of the counts of Andeška. transferred to Kamnik, and from there to Ljubljana after the extinction of the Andeška family.

The Counts of Andeška also granted Kranj city rights, so the citizens of Kranj are mentioned as early as 1221, and Kranj as a city (civitas) for the first time in 1256. This meant many benefits in trade and crafts, especially trade in agricultural products and ironworks. Kranj also received a coat of arms (the eagle) and a flag (burgundy-silver) from the Andeška family.

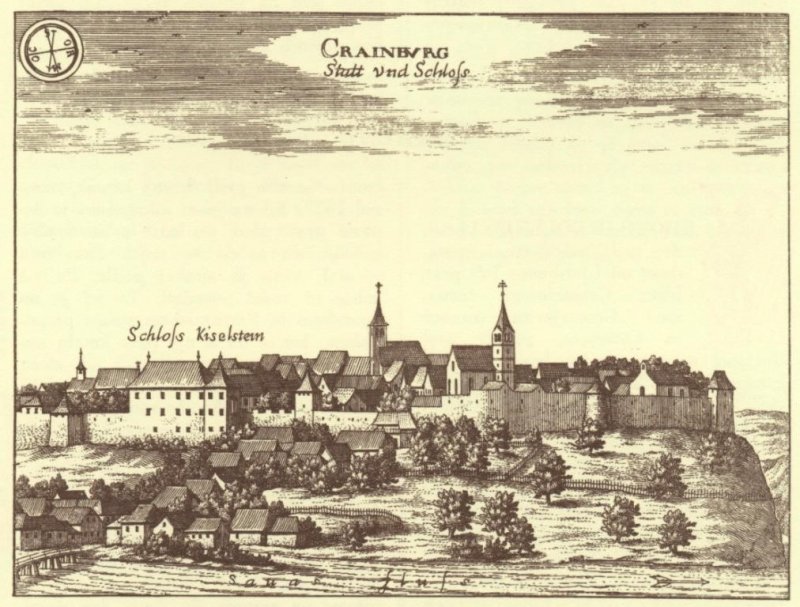

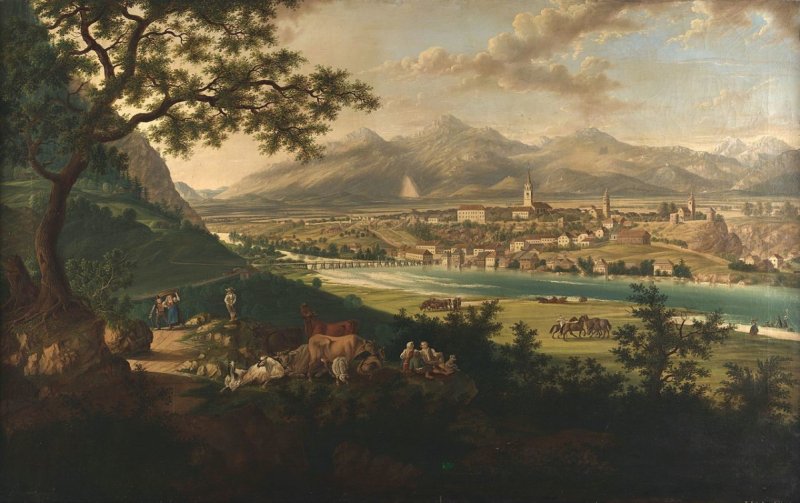

The urban design of the medieval town developed along the central road, which entered through the entrance tower on the north side, and which connects today's Maistrov trg (created after the fire of 1811), Glavni trg, and Trubarjev trg. The building plots of merchants and craftsmen were lined up perpendicular to it. The original passages between the buildings were gradually filled with new buildings, so the parallel economic routes on the Kokra and Sava sides became increasingly important. The new defensive wall was based directly on the wall built during the late antiquity, and during the Turkish threat at the end of the 15th century it received several new towers and a fortified northern part.

After the abandonment of the walls in the 17th century, the building complex of today's Tomšičeva Street was finally formed. Craft workshops of leatherworkers, millers and blacksmiths leaned into the Sava suburb of today's Vodopivčeva Street, where the lower city gates led. The view of the city is also extremely thoughtfully designed, as the height dominants of the bell towers and towers are combined into a triangular composition, which is also emphasized by the mountains in the background.

The town was enriched in the middle of the 15th century with an exceptional late Gothic architectural masterpiece of the parish church of St. Kancijan and the Companions of the Martyrs, who became an example for many new churches in Carniola. Khiselstein Castle developed from the former Ortenburg tower above the most favorable passage across the Sava, the current image given to it by the Khisl family in the middle of the 16th century and extensions from the 18th and 19th centuries.

The town is also adorned by many rich Renaissance bourgeois buildings with arcaded courtyards and a series of buildings with pier floors in front of the parish church. The town hall, which consists of its northern, late Gothic part and the Renaissance part with a hall added to it, also found its place on the main square. The hall represents the most beautiful Renaissance interior in Gorenjska. The former palace of the noble families Ausperg and later Ecker leaned on the town hall complex. The 15th century also added both branch churches – Roženvenska (Rosary) at the top of Vodopivčeva street and the church of Saints Rok, Fabjan, and Boštjan on Pungart.

The most important economic activities in the Middle Ages were the milling along the Sava and Kokra, butchery, mechanical engineering, leather, and various metal processing trades. With fair privileges, Kranj also tried to gain a monopoly over trade and individual crafts. Significant revenues were generated by the weekly grain fair, which was the largest in Inner Austria and significantly determined the price of grain.

Significant stagnation in economic development was brought about by the 16th century with peasant uprisings and the Reformation, as well as the 17th century, when the city lost its monopoly over crafts and long-distance trade. Plagues and numerous fires added their share (in 1668 a third of the houses burned down, in 1749 almost the entire town burned down, and in 1811 its northern part). Only the reforms of Maria Theresa strengthened the city's economy again. Napoleon's occupation in 1810 brought an entire secondary school to the city for a short time.

The cultural and national awakening in the 19th century was marked by the poets France Prešeren and Simon Jenko living in Kranj and the writers Janez Mencinger and Ivan Tavčar. In 1897 the grammar school was revived. The arrival of the railway in 1870 was a strong economic stimulus. With the appearance of manufactories and, at the end of the 19th century, industry as well, Kranj became an increasingly industrial city. After the First World War, the textile industry experienced a special boom, settling in the depths along the Sava and in the fields in Stražišče and Primskovo.

During World War II, housing construction first spread beyond the old borders to the left bank of the Kokra. After the war, Kranj maintained its position as the administrative centre of Gorenjska, and the successful development of the rubber, textile, electrical, and footwear industries greatly accelerated the growth of the population. This was followed by the expansion of non-economic activities - education, health, culture, and the explosion of urbanization in the form of new dormitories in Zlato Polje and Planina.

Slovenia's independence initially brought the collapse of many labour-intensive industries (textiles, footwear), but was soon replaced by the private retail economy, trade, services, the electrical industry, and rubber.